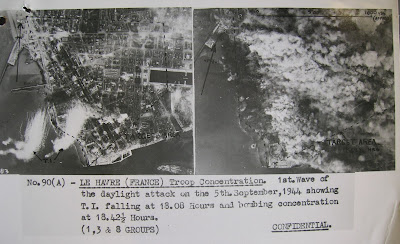

Aerial photographs to assess the effectiveness of the R.A.F. on one of the raids of 5th September on Le Havre

Prior to D-Day for the investment of Le Havre, i.e. 9th

September, the defences of the port, as described earlier, were to be ‘softened

up’. This was to be achieved by close cooperation between Bomber Command of the

R.A.F., the Royal Navy and the massed Artillery Regiments supporting the 49th

and 51st Infantry Divisions.

The mammoth task to disrupt the defences and to reduce the

capability of the garrison to withstand the landward assault commenced on 5th

and carried on through to the 7th September. Over this period, a

total of 8,300 tons of high explosive were dropped on the target zones.

However, the bombing raids conducted over the nights of the 5th and

6th killed an estimated 5,000 French citizens, many of whom perished

when the R.A.F. bombed a residential area of the city. On 31st

August, the Fortress Commandant, Oberst Hermann-Eberhard Wildermuth, ordered the

remaining citizen population to leave the city, but this order was countered by

the Maquis who posted notices urging the civilians to stay in order to prevent

the anticipated mass pillage of property by the remaining German Army. Thus it

was that the numbers of civilians still resident in Le Havre was high upon the

start of the Allied bombardment.

Earlier in the week, with the knowledge that a large scale

Allied attack on Le Havre was an inevitability and knowing British

sensitivities towards collateral damage in terms of French citizens, Widermuth

appealed to the British then amassing in front of the city’s outer defences.

Two senior officers of 1/4 King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) of 146 Brigade were requested to escort two German officer envoys by staff car to Brigade HQ. The envoys carried a message from the Fortress Commander requesting that the Allies permit the evacuation of the remaining civilians (estimates to be in the order of 20-30,000 as of the end of August) prior to the battle. The German officers explained that Hitler's personal orders were that the port of Le Havre was to be defended 'to the last man and the last round'. As for the Allies, they were adhering to a policy of unconditional surrender. Brigadier Johnnie Walker telephoned Wildermuth's proposal through to GOC General Sir Evelyn 'Bubbles' Barker. The proposal was turned down with the words 'I wish you good luck and a Merry Christmas'.

Oberst Hermann-Eberhard Wildermuth

Fortress Commandant of Le Havre

The night raid of 6th September, involving

Lancaster and Halifax aircraft numbering one thousand, unleashed 1,500 tons of

explosive, a large proportion of which was targeted upon the Grand Clos Battery

in Bréville located to the north of the centre.

The devastation of the city wrought by the by the R.A.F.

could actually have been more extensive, but the bombing campaign was hampered

by appalling weather. The unfavourable conditions were such that D-Day for

Operation Astonia was postponed by 24 hours from the 9th to the 10th

September.

The combined firepower of the three arms of the Allied Armed

Forces resumed the bombardment on Sunday 10th, ahead of the

start of the infantry assault. A series of timed bombing waves was set that

targeted specific regions of the city's defences.

- Alvis - duration: 1645 to 1745 over the Northern defences

targeting exterior wire positions and anti-personnel defences

- Bentley – duration: 1845 to 1900 over the Southern plateau

defences targeting barracks and fort positions with high explosive

- Buick – duration: 1900 to 1930 with the same objective as

Bentley but over the Western defences

- Cadillac – duration: D+1 to end at 0800 on 11th

September targeting the Western defences (the installations of the harbour

areas) with high explosives.

Map of the port showing the target zones for the successive bombing waves (shaded)

The total payload dropped on Le Havre on 10

th

September was 4,719 tons from 992 air

craft.

Off the coast the monitor class battleships, HMS Erebus and

HMS Warspite, once again opened up the naval bombardment ‘on the casemated guns

on the perimeter defences of Le Havre’. The hit rate of both ships was

impressive according to the reports of spotter aircraft over the port area.

HMS Erebus in 1944

HMS Warspite in 1944

Eventually, HMS Warspite was credited with silencing the three 17cm guns and

one 38cm gun of the Grand Clos Battery.

The 38 cm gun of the Grand Clos Battery

Vertical photographic-reconnaissance taken over Le Havre, France after daylight raids by aircraft of Bomber Command on 5, 6 and 8 September 1944. A large area of devastation can be seen in the city centre west of the Bassin de Commerce, over which smoke from burning buildings is drifting. Further attacks on and around Le Havre were carried out on the three following days in an effort to reduce the German garrison still holding out in the city © IWM (C 4601)

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205023343

The bombardment by air, sea and land earned Le Havre the dubious distinction of being the most damaged town in France with 82% of it declared as destroyed. This accounted for 12,500 buildings left beyond repair and 4,500 partially destroyed. The bombings of 5th to 12th September rendered half of the civilian population homeless.

With echoes of the bombing of Caen three months previously, a tremendously high price had been paid in terms of civilian casualties and destruction of properties for limited military gain. In Oberst Wildermuth's words after capture:

' The air bombardments and the shelling from the sea had only a general destructive effect, but did not create much military damage. The real effective fire came from the Allied concentrated artillery which had devastating results in knocking out the guns of the fortress'.

Crucially, what the concerted bombardment did achieve was an almost complete disruption of the German's telecommunication systems within the city which severely hampered the capability to coordinate the defence.